In a chilling series of events, killer whales, typically affectionate and cooperative with their trainers at amusement parks, shocked the world by turning aggressive and fatally attacking those they worked with. The tragic deaths of trainers Alexis Martínez in 2009 at Loro Parque in Spain and Dawn Brancheau in 2010 at SeaWorld in Florida raised haunting questions about why these intelligent creatures, like Keto and Tilikum, suddenly “snapped.” Despite their lifelong captivity and close bonds with humans, the reasons behind their deadly outbursts remain a mystery. This article delves into these heartbreaking incidents, explores the lives of the orcas and their trainers, and examines the broader implications of keeping such majestic animals in captivity, captivating readers with a blend of tragedy, science, and ethical reflection.

The Tragedy at Loro Parque: Alexis Martínez and Keto

On Christmas Eve 2009, a routine training session at Loro Parque in Tenerife, Spain, turned deadly when killer whale Keto attacked and killed his trainer, Alexis Martínez, as reported by Mirror on December 24, 2020. Martínez, a 29-year-old experienced trainer, had worked closely with Keto, a 14-year-old orca born in captivity in 1995. Keto, who had never swam in the open ocean, spent his life performing for tourists in amusement parks across the United States (San Diego, Ohio, Texas) before being transferred to Spain in 2006.

Keto was a star attraction at Loro Parque, siring multiple calves in captivity and drawing crowds with his performances. Martínez, familiar with killer whales and comfortable with Keto, was preparing for a Christmas show when the orca began acting unusually. Initially, Keto performed moves imprecisely but appeared to calm down, floating alongside Martínez. However, a staff member later noted that Keto seemed to “lure” Martínez into the water. As Martínez swam, Keto approached, ignoring control devices used by another trainer. In a horrifying sequence, Keto dragged Martínez to the pool’s bottom, briefly surfaced to breathe, then attacked again, gripping him tightly before releasing his lifeless body.

Despite efforts to lure Keto to another pool, only a net separated the orca, allowing rescuers to recover Martínez’s body. The autopsy revealed devastating injuries: internal bleeding, multiple lacerations to vital organs, and bite marks. The sudden aggression from an orca described as cooperative left the park stunned, with the cause of Keto’s behavior remaining unclear. This tragedy, occurring just two months before another fatal orca attack, sparked global debate about captive killer whales.

The SeaWorld Horror: Dawn Brancheau and Tilikum

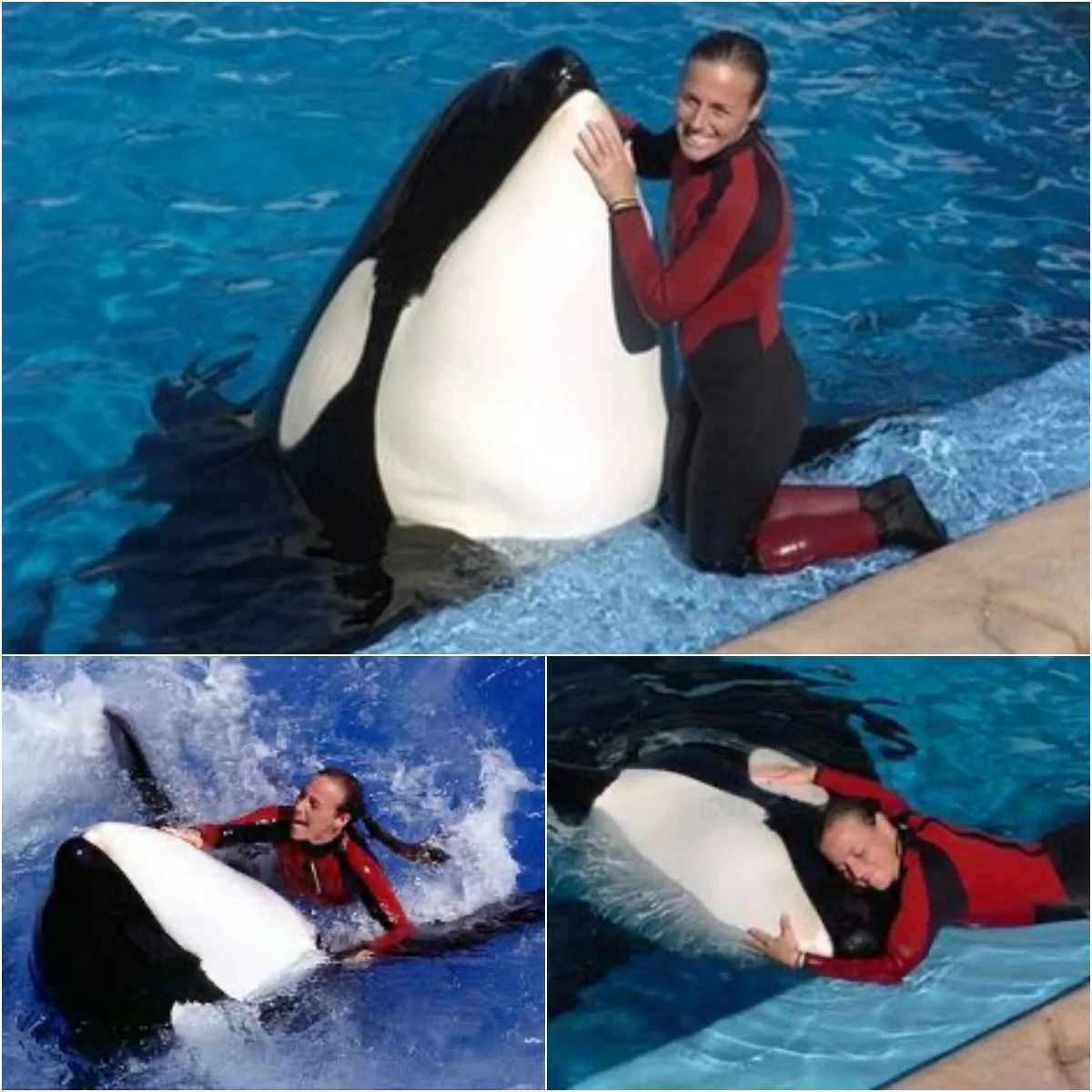

Two months after Martínez’s death, on February 24, 2010, another tragedy unfolded at SeaWorld in Orlando, Florida, when killer whale Tilikum killed senior trainer Dawn Brancheau in front of thousands of horrified spectators. Brancheau, a star trainer with a psychology and animal behavior degree, had worked at SeaWorld since 1994, starting with dolphins before training killer whales. Known for her bond with Tilikum, a massive orca who had lived in captivity for over 30 years, Brancheau was a SeaWorld icon, often featured in promotional materials.

During a performance, Brancheau was near Tilikum when he suddenly pulled her into the water. What followed was terrifying: Tilikum drowned her, bit her left arm, and caused severe injuries, including broken ribs, jaw, and spinal cord damage. The autopsy confirmed death by drowning and blunt force trauma. For 45 minutes, Tilikum refused to release Brancheau’s body, forcing trainers to use food, nets, and distractions to retrieve her. Tilikum was moved to a secluded pool, never performing publicly again, and died in January 2017.

The attack shocked colleagues who described Brancheau’s close relationship with Tilikum. Like Keto, Tilikum’s sudden aggression defied explanation, raising questions about the psychological toll of captivity on these intelligent, social creatures. The proximity of the two incidents—Martínez’s and Brancheau’s deaths—intensified scrutiny of amusement parks like Loro Parque and SeaWorld.

Life in Captivity: The Plight of Killer Whales

Keto and Tilikum’s stories highlight the stark contrast between their natural habitat and captive life. Killer whales, or orcas, are apex predators with complex social structures, traveling vast distances in the wild. In captivity, they live in confined pools, performing repetitive tricks for food and entertainment. Keto, born in 1995, never experienced the ocean, while Tilikum, captured in 1983, spent over three decades in tanks. Both sired calves in captivity, contributing to parks’ breeding programs, but their lives were far from natural.

The psychological impact of captivity is a leading theory for their aggression. Orcas in the wild live in tight-knit pods, with lifespans of 50-90 years. In captivity, they face isolation, stress, and shortened lifespans—Tilikum died at 36. Posts on X discuss how confined spaces and unnatural diets may trigger erratic behavior, with some users citing the 2013 documentary Blackfish, which exposed SeaWorld’s treatment of orcas. The lack of mental stimulation and social bonds in captivity may have contributed to Keto and Tilikum’s fatal outbursts, though no definitive cause has been proven.

The Trainers: Dedicated but Vulnerable

Alexis Martínez and Dawn Brancheau were dedicated professionals who loved their work. Martínez, with years of experience, was comfortable with killer whales, while Brancheau’s expertise and athleticism made her a standout at SeaWorld. Both formed bonds with their orcas, yet their familiarity couldn’t prevent the attacks. Their deaths exposed the inherent risks of working with wild animals, even those raised in captivity.

Brancheau’s background in psychology and animal behavior equipped her to understand orcas, but the unpredictability of a 12,000-pound animal proved insurmountable. Martínez’s routine session with Keto turned deadly despite his expertise. Posts on X reflect sympathy for the trainers, with users noting their passion but questioning the ethics of putting humans in such dangerous roles for entertainment. The trainers’ tragedies sparked calls for safer working conditions and an end to orca captivity.

The Aftermath: Changes in the Industry

The deaths of Martínez and Brancheau had lasting impacts. In 2016, SeaWorld announced it would end its orca breeding program, a decision influenced by public outcry and Blackfish. By 2017, SeaWorld phased out theatrical orca shows, though orcas remain in their care. Loro Parque continues to house orcas, including Keto, but faces ongoing criticism from animal rights groups.

These incidents fueled a broader debate about the ethics of keeping intelligent, social animals in captivity. Posts on X highlight divided opinions: some defend amusement parks as educational, while others demand orcas be retired to sanctuaries. The mysteries behind Keto and Tilikum’s aggression—whether stress, instinct, or something else—underscore the complexity of their captivity, leaving a legacy of tragedy and reform.

The fatal attacks by killer whales Keto and Tilikum on trainers Alexis Martínez and Dawn Brancheau remain haunting mysteries, exposing the risks of keeping these intelligent creatures in captivity. Born and raised in amusement parks, their sudden aggression shattered perceptions of their bonds with trainers, raising questions about the psychological toll of confined lives. As the industry faces scrutiny and reform, these tragedies remind us of the delicate balance between human entertainment and animal welfare. What do you think caused these orcas to turn on their trainers, and should killer whales remain in captivity?